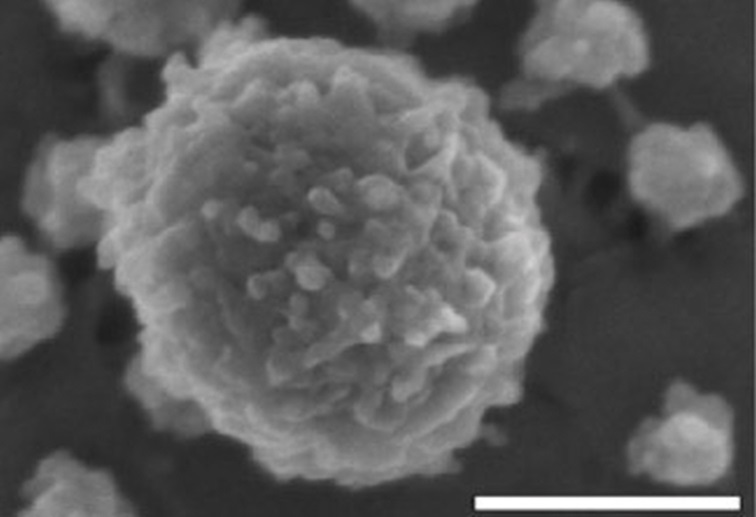

Micelle on the microscope (Hristov et al., 2015)

Micelle on the microscope (Hristov et al., 2015)

How does milk can turn into cheese? Why can’t we make cheese with any type of milk? In this article I try to explain the chemical and physical processes that happen in cheesemaking.

To simplify things, in this article milk refers generally to cow milk. But actually, those principles apply to different types of milk if they have the right characteristics (see further), like goat, sheep, buffalo milk to name a few.

This article is largely inspired by the popularization work of Florian Ronez on milk coagulation. If you are interested into making cheese curd, follow this article.

Milk composition

To understand cheesemaking it is important to first understand what is milk. There exists different types of cows that have been selected by humans for several milleniums for milk and cheese production. Those cows are called Holstein, Jerseys, Montbéliardes, Simmental etc. Those different breeds yield between 7.000 and 12.000 liters per year. Milk composition for these different breeds can vary slightly. The amount of proteins varies between 3% and 2.6% and fat between 3.7% and 4.8%. These differences can have a huge impact on final cheese product though! Pasterization and time after milking also affect the concentration of certain protenis and vitamines. In average, cow milk contains:

- 88% water

- 3.2% proteines (among which 80% of caseins)

- 4.8% carbohydrates (among which 97% of lactose)

- 3.2% fat (among which 98% of triglycerids)

- minerals (calcium, potassium and phosphore essentially)

- vitamins (B12, B2 and A essentially)

Proteins

Casein micelles

The proteins called caseins constitute about 80% of milk proteins. They are soluble in water (hydro-phobic). Caseins are fundamental in milk:

- they allow to keep calcium in suspension in milk and thus to make it a very good source of calcium (otherwise calcium would just precipitate)

- they are a key element in cheesemaking

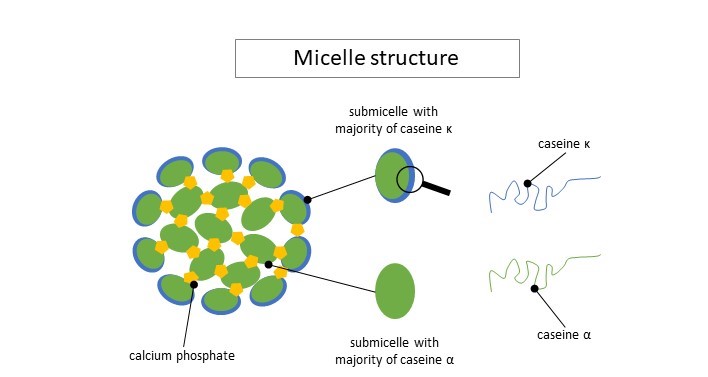

There exists different sorts of caseins: αS1, αS2, β et κ. They all have different roles in cheesemaking. Those proteins have different “attraction” for water and calcium. Through a mechanism of attraction/repulsion, those proteins agglomerate into small heterogeneous blobs called submicelles (see figure below). Those submicelles then aggregate into bigger units of 10 to 100 submicelles called micelles. Some submicelles contain more or less α-casein and other contain more κ-casein. The latter are less hydrophobic than the others and keep on the edges. The other ones keep in the center of the micelles. Calcium and phosphate also interact with submicelles and help keeping them together.

Illustration largely inspired by Le lait et sa coagulation, Florian Ronez

Illustration largely inspired by Le lait et sa coagulation, Florian Ronez

For more details about the micelles structure and chemical aspects please refer to the references at the end of the article.

Whey proteins

The remaining 20% of milk proteins are essentially albumines and globulines. Those proteins are soluble in water. They do not coagulate during milk curdling. They keep in the whey. Those proteins coagulate when heated though (like albumines of the egg whites do when cooked). You can retrieve those proteins by cooking the milk slowly. That is what is done to make ricotta for instance.

Coagulation

Coagulation is a general term describing the transformation of a liquid into a solid mass. When speaking about milk, coagulation is the processus that separates milk into curd (a sort of soft mass) and whey or lactoserum (a liquid). This process can be the result of:

- a lactic fermentation from bacteria

- an enzymatic reaction (usually from rennet)

In both cases, coagulation corresponds to a destabilization of the micelles and their merging. For most of cheeses, both coagulation types are generally involved in curdling. However both types may be more or less strong. For instance, fromage blanc, Saint-Marcellin and goat cheese have a stronger lactic fermentation than enzymatic. That is why we offen refer to those cheeses as lactic cheeses. Hard cheeses like tomme or cheddar go through stronger enzymatic coagulation. We see later how this has a strong impact on the cheese moisture.

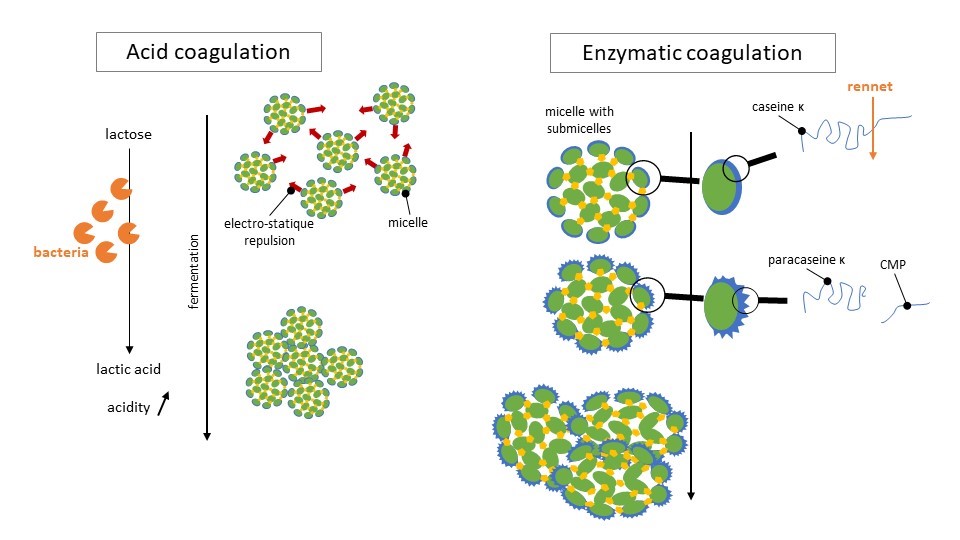

On the figure below we show how those two mecanisms work.

Illustration largely inspired by Le lait et sa coagulation, Florian Ronez

Illustration largely inspired by Le lait et sa coagulation, Florian Ronez

In the case of lactic fermentation, bacteria transform the lactose into lactic acid. Milk acidity increases which decreases the repulsion effect between micelles. Those ones end up agglomorate together, to sort of “escape” water. The resulting solid mass is curd!

When rennet is added, another mecanism operates. Rennet is made of enzymes that cut κ-caseins that are at the border of the micelles into para casein κ and a fragment that will precipitate in the whey. The micelles are then destabilized. The para casein κ becomes more hydrophobic and then connects with α-caseins. The micelles then get closer to each others. This step is called floculation. After some time, the micelles organize into a very well structured network: the curd.

Can we make cheese from any milk?

The last paragraph shows the essential role of caseins into making curd, which is the base element of most cheeses. The casein content of milk must thus be sufficient to turn the milk into cheese. The milk of cows, goats, sheeps, buffalos, reinders, yaks and zebus contain enough caseins to be turn into cheese. However this is not the case for camels or human milk… Moreover, there can also be slight differences between cow breeds. For instance, Jersey cows give a milk that is richer in proteins than Holstein (the most common cow breed). Their milk is thus ideal to make good cheese!

Draining or syneresis

Milk has now coagulated, it has turned into curd. Curd looks a bit like jelly (see this article for pictures). It has then to be drained to remove more or less moisture (depending on the type of cheese you want to make). The goal of draining is to remove whey from the curd.

Given the coagulation type (as described above), the curd has a different structure. Lactic fermentation gives a weakly structured curd. This makes draining spontaneous, slow but also incomplete.

On the other hand, enzymatic coagulation gives a strongly structured curd. The micelles network keeps the whey into small pockets, which makes draining more difficult. To remove more whey, you thus have to apply:

- a physical action like cutting, stirring, pressing

- a chemical action like warming up or salting

When making a tomme for instance, the curd is cut into very small pieces, stirred, warmed up slightly and pressed. Those four actions help eliminating moisture from the cheese.

Curd structure has also an influence on cheese evolution, but we will see that in another article!

References

- La composition du lait, Wikipedia

- Le lait et sa coagulation, Florian Ronez

- Measurement of Casein Micelle Size in Raw Dairy Cattle Milk by Dynamic Light Scattering , Hristov et al., 2015

- Casein micelle structure: a concise review, Phadungath, 2005

- The Science of Cheese, M. H. Tunick